Tropic Sprockets / The Pigeon Tunnel

By Ian Brockway

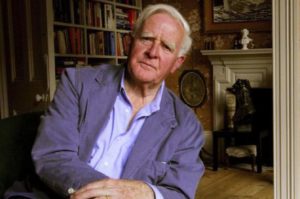

Errol Morris (The Fog of War) offers an arresting portrait of the writer John le Carré in “The Pigeon Tunnel.” We see le Carré as a sophisticated and reserved British gentleman of the upper classes, but appearances are not as they seem. Behind the author’s unflappable reserve, there is pain and some regret, but le Carré puts up a disinterested yet congenial front throughout. This engaging and somewhat puzzling documentary draws us in precisely because of the subject’s cool exterior.

John le Carré was born David John Moore Cornwell on October 19, 1931. His father was a con man and a fraudster who went to jail numerous times. His mother Olive left the family when the author was five years old. In part due to his father’s criminality, le Carré did not fit in with English conventions. He gradually realized that he could achieve success through seeing life as a great performance art, and pretending, by acting the part as if on stage.

The method worked. Le Carré got enrolled into Saint Andrews preparatory school and became a student of languages at Oxford. From there he married and became a teacher at Eton. Despite his academic existence, other lives beckoned, most acutely the life of an intelligence officer, or a spy. Britain at the time was smitten with pop culture images of James Bond and glamour. In reality, le Carré states, nothing could be farther from the truth. Actual agents were dysfunctional and somewhat defective people, using a life of espionage to escape from themselves to become someone else: a servant with many façades.

Throughout the film, le Carré dismisses his own accountability as a spy, saying he was essentially driven to choose the occupation and had no choice. One is inclined to agree. Le Carré rejects being on the just or good side of things. Further, the concept of truth is subjective and does not exist in certainty. “What is truth?” asks le Carré. “What is memory? We ought to find other words.”

The author’s memory is invested with images of his father looking out at him from prison, only to later admit that such a memory would be impossible due to the prison’s construction. Le Carré’s mother, only half glimpsed in sleep and barely touched by a capricious leather glove becomes a figure from the cinema, a siren, magical and unreal. Interspersed in the film are film clips from the author’s adaptations, combined with Morris’s trademark deep focus camera work, where a telephone or a bureau desk becomes gigantic in proportion.

Le Carré dismisses any question of lasting unhappiness, or familial resentment. He actively chose his espionage, and this turn led him to a life of creativity and imagination. The author is titanium-minded to the end, a life of an artist is in itself a revenge and the best reward possible, a defense against his father’s oppression and physical abuse. Errol Morris portrays his subject as he is: unsentimental, resourceful, and reserved, a man of varnish and veneer with an acceptance of the shifting and porous multiples of existence, a spy with a gimlet eye.

Write Ian at [email protected]

[livemarket market_name="KONK Life LiveMarket" limit=3 category=“” show_signup=0 show_more=0]

No Comment